John had been dead for three days when Ephraim Trembly discovered his brother in rural Maryland.

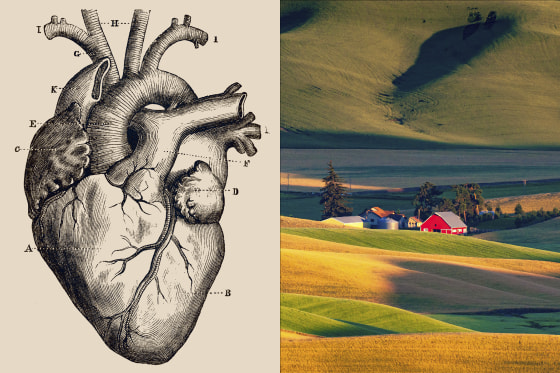

Their father, John Trembly Sr., claims that they could only identify John from a tattoo because his corpse was so deteriorated that it was unclear how he passed away. According to his father, John overdosed because the coroner discovered traces of fentanyl. However, the autopsy also revealed something more peculiar: John’s cardiovascular system had been wrecked at the age of 20.

John had lived most of his life in Terra Alta, West Virginia, a hamlet of less than 1,500 residents, until his death last year.

One in five Americans live in rural areas, and because of heart disease and strokes, they often live three years less than their urban counterparts. And according to study released this month in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology, this gap grew between 2010 and 2022, primarily due to a 21% rise in cardiovascular deaths among working-age rural persons.

According to the study’s main author, Dr. Rishi Wadhera, a cardiologist at Boston’s Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, this is the first nationwide examination of rural cardiovascular health during COVID-19. Deaths from heart disease and stroke had been declining in both urban and rural areas before to 2019, but they skyrocketed in 2020 when the pandemic struck, undoing decades of progress.

According to Wadhera, it is unacceptable that cardiovascular death rates among young adults are rising across the nation.

The findings, according to Dr. Chris Longenecker, director of the University of Washington’s global cardiovascular health program in Seattle, aren’t particularly shocking because cardiovascular mortality has historically been higher in rural areas due to a confluence of factors, such as drug use, ill health, and limited access to care. However, the findings raises new concerns about what is causing these growing gaps and whether there is anything that can stop the bleeding.

According to Trembly Sr., no one wants to watch their 20-year-old son die when they still have their whole lives ahead of them. Simply put, it’s unfair.

Drivers of the rural-urban divide

Wadhera and his colleagues looked at death certificate data for more than 11 million persons by age in their study. Cardiovascular deaths among those aged 25 to 64 rose between 2010 and 2022, while those aged 65 and above saw a decline. Compared to their urban counterparts, the rises happened more quickly and the declines more slowly in rural communities.

These discrepancies can be attributed, in part, to variations in the underlying risk variables. Over the past ten years, younger persons have been more likely to develop obesity, diabetes, and hypertension, with rural areas being disproportionately affected, according to Longenecker. This is linked to systemic problems, such as a lack of access to fresh food and gyms, a higher unemployment rate, and a lower level of health knowledge.

According to Dr. George Sokos, chair of the cardiology department at West Virginia University, the opioid crisis has also had a particularly negative impact on small towns and rural areas, which has not only made people’s financial circumstances worse but also directly contributed to heart disease mortality. Methamphetamine and cocaine stimulant overdoses have also been on the rise, nearly doubling in number between 2012 and 2022.

According to his father, John used to clean businesses at night and rental homes during the day. He used methamphetamine to remain awake and work more quickly in order to meet the demanding timetable. John also took over his girlfriend’s cleaning duties during her month-long hospital stay, making the two-and-a-half-hour drive to see her every day.

According to the senior Trembly, he was managing the workload of two individuals. Her hospitalization was unknown to his supervisor.

But meth is also linked to stroke and heart disease. According to his father, chronic use probably damaged John’s cardiovascular system and may have played a role in his demise.

The lack of access to healthcare in rural areas makes all of these issues worse.

According to Sokos, our state struggles to recruit primary care doctors, which makes it more challenging to avoid cardiovascular disease or to act early. Not to mention that there aren’t enough cardiologists to handle complicated situations and manage these illnesses. He went on to say, “We can’t reach some of these younger patients early enough.”

These problems were exacerbated by the Covid pandemic; according to Wadhera’s research, between 2019 and 2022, cardiovascular mortality increased by 8.3% in rural areas and 3.6% in urban areas.

According to Longenecker, the pandemic is an outside stressor that exacerbated all of those underlying societal variables.

For instance, during the pandemic, overdose mortality rose as a result of people turning to drugs as coping techniques and treatment resources being disrupted. Preventive screenings and hospitalization rates for heart attacks and strokes fell sharply as a result of hospitals being overburdened by COVID patients and, in rural areas, closing at record rates.

According to Wadhera, there were more than just inconveniences since hospitals were under pressure. A lot of people were simply afraid to seek medical attention in hospitals or other healthcare facilities.

Although telehealth was meant to close this gap, data indicates that it may have made inequities worse by leaving rural regions without internet access behind. In fact, less than half of West Virginians with access have high-speed internet, and more than a third do not.

According to Sokos, my patients will pull into the gas station parking lot, connect to the internet, and conduct a phone telehealth appointment. The patients desire the care, but they are unable to receive it.

Solutions ahead

Innovation is not the answer to stopping the increase in heart disease and strokes in rural America.

Here, we’re performing state-of-the-art medical procedures, including robotic surgery that no one else in the nation is performing, Sokos stated. However, getting on the ground and reaching the patients to provide basic treatment is equally critical.

According to Dr. Jeremiah Hayanga, a cardiothoracic surgeon at West Virginia University, the university has attempted to address some of these problems by increasing the number of physician assistants and nurse practitioners it employs and sponsoring visas for foreign-trained medical professionals visiting the state.

According to Hayanga, the university also intervened during the epidemic to buy failing rural hospitals in order to preserve access to healthcare throughout the area.

According to Longenecker, a community-driven strategy is necessary for any future direction. In order to achieve this, he leads a research network that aims to adapt lessons learned from the delivery of healthcare globally to rural communities in the United States.

In one experiment, individuals who have undergone addiction treatment are trained to conduct heart failure tests on meth users in the community.

Another provides community health workers with ultrasound equipment so they may perform heart disease screenings on individuals.

According to Longenecker, this strategy has been used in Uganda to detect illnesses early and stop their progression. “So, why couldn’t it work on Native American reservations as well?” he went on.

According to Longenecker, the overall goal is to remove geographical restrictions and provide cardiovascular treatment closer to people’s locations. Black Americans are increasingly receiving blood pressure checks at barbershops in the United States, while African nations have done the same with remarkable success, offering HIV care in community settings.

What is the barbershop equivalent in rural America? Longenecker inquired. Taking care of hypertension is not difficult; you can do a lot of it in the community, whether it be at the church, library, or another location.

“Active engagement with rural communities is at the core of this work,” he stated. After all, the experiences of people in the Cherokee Nation will be completely distinct from the Alaskan frontier, or from Black Americans in the rural South a region sometimes called thestroke belt. One key limitation of Wadhera s paper is that it doesn t examine race and ethnicity data, or geographic differences among states. However, there is where the practical labor becomes important.

Is it possible to do rigorous implementation science in remote areas? In other words, how should the delivery of health services be reorganized in your community to address these disparities? Longenecker inquired.

An uncertain future

Better health care delivery will certainly help address rural cardiovascular disparities but won t necessarily address the underlying socioeconomic drivers.

This is previously a community that s steeped in coal mining, said Hayanga, noting that West Virginians are now struggling as those jobs have disappeared without much to replace them. We need to support the local community so that they are able to make a living.

Still, both Hayanga and Longenecker have hope, seeing new interest and research funding into rural-urban disparities, as well as a greater national spotlight on this issue.

In Congress, you have many of these more rural states represented by the Republican Party, which is now in power, Longenecker said. I ll be curious to see how this influences policy decisions around rural health.

But any change will come too late for John Trembly Sr. and his late son.

What can we do? How can we help? All you can do is just stand back and watch, he said. It would be nice to have a way where we could help our loved ones more.

Note: Every piece of content is rigorously reviewed by our team of experienced writers and editors to ensure its accuracy. Our writers use credible sources and adhere to strict fact-checking protocols to verify all claims and data before publication. If an error is identified, we promptly correct it and strive for transparency in all updates, feel free to reach out to us via email. We appreciate your trust and support!