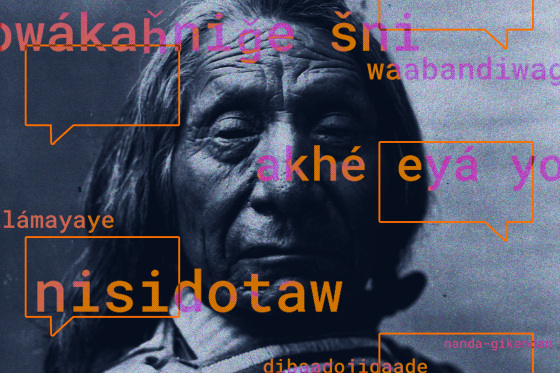

The clock is ticking for indigenous researchers: Every two weeks, one of the 4,000 indigenous languages spoken around the world passes away. According to Michael Running Wolf, creator of Indigenous in AI, an international network of Native, Aboriginal, and First Nations engineers, the majority of Native American languages in the United States may disappear within the next five to ten years.

Preventing this loss has been the focus of Running Wolf’s career. He is the director of the Mila-Quebec Artificial Intelligence Institute’s First Languages AI Reality program, where scientists are developing speech recognition models for more than 200 North American Indigenous languages that are in danger of extinction.

He must first get past a significant obstacle, though: there aren’t enough Indigenous computer science graduates who are familiar with the language and culture to work on these language preservation initiatives. Indigenous scientists are aware of the need of respecting the data itself, Running Wolf underlined. “The core data we use is deeply culturally identifying information from speakers who may have passed away; it’s not just tweets or social media posts,” he said. We must ensure that the community maintains its connection to the data at all times.

According to Running Wolf, he has only encountered perhaps a dozen Indigenous North American AI experts in his years of research. According to him, we only award one or two Indigenous Ph.D.s in computer science and artificial intelligence per year.

Only 0.4% of computer science bachelor’s degrees are awarded to Indigenous people annually, they comprise less than 0.005% of the U.S. tech workforce, and there is only one board member in the top 200 tech companies. Just 0.02% of venture capital investment went to Native-founded businesses in 2022.

The few Indigenous engineers that do exist fill that gap by spearheading initiatives like First Languages AI Reality, Indigenius, Tech Natives, and the Wihanble S, a Center for Indigenous AI, which trains computer science students who are Native American, Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian in order to preserve Indigenous culture and language.

According to Running Wolf, AI has historically assumed that data is proprietary, which can be detrimental to Indigenous communities. We hope to show that ethical AI standards can help us achieve our goal of regaining Indigenous languages in an ethical manner.

Building the Indigenous-tech pipeline

Tech Natives, a group of Indigenous women in technology that provides recruitment and mentorship opportunities on college campuses, has dozens of beneficiaries, including Kyra Kaya.Kaya, a Yale University computer science student, was motivated to create an AI tool in memory of her Native Hawaiian grandmother, whom she spent summers on Maui with. The 20-year-old added, “I realized that many Native Hawaiians don’t have access to technology that many people take for granted.”

The tool was fed by her. Many Hawaiians speak Hawaiian Pidgin English, a highly stigmatized English-based creole language that has been trained to detect spoken phrases. She stated, “I wanted to shift the narrative around pidgin as a lesser language.” I entered words that my mother, grandmother, and aunts used, and it recognized them.

Kaya wants to develop her work into an app that other residents of Hawaii can use. According to her, AI and the tech sector have the ability to either empower or suppress underrepresented communities like mine. Indigenous people can and should have a significant role in it because of this.

According to researchers, encouraging Indigenous people to pursue careers in technology at an early age is the first step in increasing their participation in the field. Every summer, IndigiGeniusLakota AI Code Camp in South Dakota brings together Native teenagers for three weeks to create an app that chronicles Lakota culture, including common Lakota terms and sacred plants. 33 students have been trained to contribute to the app since the code camp began in 2022; many of these students have gone on to become instructors or work on other computer science initiatives.

IndigiGenius has also started T3PD, which trains 20 high school teachers nationwide—the majority of whom are Native—to create culturally appropriate computer science curricula in respective institutions in order to sustain tech education throughout the academic year.The organization is working with instructors to provide laptops and computer science classes to their pupils, as just 67% of Native students have access to a computer science course—lower than any other student population.

Andrea Delgado-Olson, executive director of IndigiGenius, stated that the goal is to make AI education culturally relevant for pupils. What makes us unique is the way we are bridging technology and our traditions by leveraging Indigenous knowledge.

Preserving other aspects of Indigenous culture with AI

Beyond language, AI is also assisting in bridging Indigenous cultural differences. Madeline Gupta rarely traveled to her Chippewa homelands as a child. However, the desire to return to her home regions became more pressing as she got older. According to Gupta, I felt as though I belonged there and that my forefathers had intended for me to be there.

According to her, many indigenous members lost touch with their heritage as the government forcibly removed them from their homes and families between 1819 and 1969. According to the 21-year-old Yale student, barely 2,000 of my tribe’s 50,000 members reside on the reservation. Thousands of students have thus not been able to see their own countries.

Gupta joined the Tech Natives program while in college and suggested a virtual reality immersive experience that would allow Native students to travel to their ancestral regions in the Great Lakes region. This past summer, Gupta flew to Mackinac Island to film and record stories from tribe elders using 3D spatial video on her phone and audio stories to go with it, thanks to support from the Aspen Institute and the Yale School of Medicine. She wants to make a virtual reality map of the island that people can click on to see local recordings.

“I want to reach people who don’t know our stories or don’t feel connected to the land right now,” she said.

Artificial intelligence is being used by artists in their creative processes in addition to cultural preservation. One of the first American Indian artists to employ machine learning in their work was Suzanne Kite of Bard College’s Wihanble S Center for Indigenous AI. I have a straightforward question: How can we use Indigenous ontologies to produce ethical art using AI? she said.

In order to process the information her family had gotten from spirits and animals in their dreams, Kite delved into the Lakota dream language. She recorded all of her dreams for three months last year, and then she used machine learning to convert them into a Lakota women’s geometric language that is frequently utilized in quilting and beadwork. She also created a graphic score for the American Composers Orchestra based on her dreams. According to Kite, I make an effort to avoid the Western personification of AI and instead explore the hyperlocal, grounded, and useful frameworks of knowledge offered by American Indigenous cultures.

Running Wolf anticipates that initiatives like his will be obsolete in ten or twenty years, even if many of these Indigenous AI projects are still in their infancy. His goal is to bring dying languages back to life and empower the next generation of Native speakers to develop moral technology. He expressed his desire that this technology will be seen as a relic from a difficult period.

Note: Every piece of content is rigorously reviewed by our team of experienced writers and editors to ensure its accuracy. Our writers use credible sources and adhere to strict fact-checking protocols to verify all claims and data before publication. If an error is identified, we promptly correct it and strive for transparency in all updates, feel free to reach out to us via email. We appreciate your trust and support!