At four months of age, Sharon Wong’s baby experienced itchy red spots on his skin and asthmatic coughs that persisted for weeks. The symptoms were written off as a recurrent cold by his initial physician. Then, one night when he was a toddler, Wong’s son ate a tablespoon of peanut soup with Thai flavors, which made him throw up and scratch his stomach. Wong called her new pediatrician in a panic, and the doctor saw the symptoms of anaphylaxis.

Wong recalled the episode from 19 years ago, and our second doctor was quite clear about the seriousness of the situation and what I needed to do: acquire an EpiPen, an allergist, and Benadryl. My son’s life was most likely saved by that.

Compared to the general population, young Asian Americans, like Wong’s son, who is currently a college student, have a 40% higher chance of developing a food allergy, which affects 6 million American children today. This discrepancy has been difficult for scientists to explain since it was initially noted in a seminal 2011 study.

One of the first studies to examine Asian American populations under the age of 18 in the United States is a new Stanford University analysis of almost half a million California pediatric records, which aims to explain why Asian Americans are especially vulnerable. According to the report, Native Hawaiians, Pacific Islanders, Filipinos, and Vietnamese are more at risk. Dr. Charles Feng, the study’s lead author, stated that Asian Americans are frequently ignored or treated as a monolith in current allergy research.

Food is a symbol of connectedness for immigrant families, whose generations are frequently separated by linguistic and cultural barriers, Feng continued. This is why it feels so vital to solve this puzzle, which is ultimately a matter of health inequality.

Why might Asian American, Pacific Islander and Native Hawaiian children be vulnerable to food allergies?

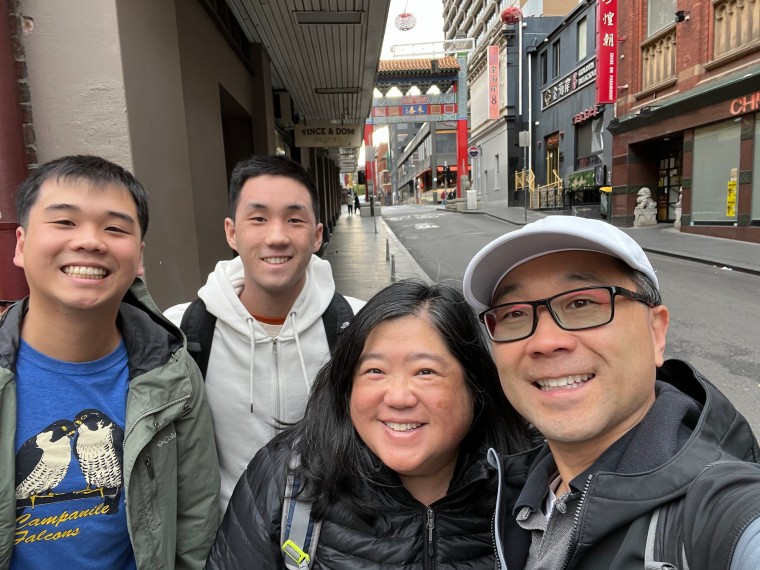

Despite having no known allergies, Wong and her husband, who reside in California, have two sons who are allergic to a long variety of foods, including peanuts, tree nuts, eggs, shellfish, sesame, tomatoes, and several fruits. Their family is representative of a larger, perplexing trend: the prevalence of food allergies among youngsters in the United States increased by 50% between 2007 and 2021.

It’s unclear how Asian American youngsters fall into this trend.They are rarely included in longterm research, which Dr. Ruchi Gupta, a pediatrician and allergist at Northwestern University, describes as a lost chance. According to her, Asian Americans, the fastest-growing racial group in the United States, offer a unique view into trends in food allergies across the country.

The sharp increase and the disproportionate effect on Asian American children cannot be explained by genetics alone. A few decades is not long enough for major genetic changes to occur. Furthermore, the same allergy patterns observed in American children with similar heritage have been found in Gupta’s studies conducted in nations like India. According to Gupta, research on Asian Americans may provide the missing piece that connects the increased allergy incidence in all children.

According to Dr. Latha Palaniappan, a Stanford University doctor who specializes in health disparities, a child’s genes most likely interact with dietary and environmental changes. For example, children’s gut microbiomes, which are crucial for immunological responses, may change as a result of consuming Westernized foods.

Granular information on food allergy frequencies within Asian American subgroups is crucial for testing these gene-environment ideas. Recent studies provide encouraging guidance, such as the recent Stanford study that Palaniappan co-authored. According to the study, the prevalence of food allergies varies significantly, with Indian American children having a 2.9% rate and Filipino children having an 8.2% rate. (The rate is 5.8% for all youngsters in the United States.) These results emphasize how crucial it is to look at how cultural norms and place of origin, such as typical cooking techniques, may affect allergy patterns.

Families must now adjust to the immediate difficulties brought on by food allergies because a large portion of the issue is still unexplained. According to Feng, the number of Asian patients with different allergy disorders is increasing. We just do not have the data to provide evidence-based care.

The cultural strains of food allergies

In just a few minutes, a youngster with a food allergy can go from appearing fine to comatose. The risks are higher for kids who don’t have a diagnosis and don’t have an EpiPen to use in an emergency.

Asian American children, who are 30% less likely to be identified with food allergies despite their increased exposure, are particularly at risk. Parents, particularly those from areas where allergies are not frequently discussed, may fail to notice warning signs, or doctors may fail to notice symptoms. According to Dr. Anna Chen Arroyo, an allergist at Stanford University, families might not identify the reaction as anaphylaxis or link it to a particular item until it gets really bad. Access to allergy care may also be hampered by cultural reluctance to seek medical advice, language hurdles, and a lack of experience with specialized services.

Managing food allergies, even after a diagnosis, frequently requires overcoming cultural barriers. Compared to other racial groups, Asian American families suffer a greater decline in quality of life due to food allergies. According to Arroyo, this is partially because of the significance of food in many Asian cultures, where communal meals serve as pillars of tradition and community.

This tension was felt by Wong. When words like “antihistamine” and “anaphylaxis” are difficult to translate into Cantonese, she combed through product labels and contacted producers of Asian cooking components. Likenian gaocake andlo han jai vegetable stew, two of her favorite childhood foods, were transformed into allergy-safe versions by her.

However, cultural festivities were particularly challenging. Sesame-coated appetizers and peanut-studded desserts are symbolic of fortune during Chinese New Year, but they were potentially fatal for Wong’s son. According to Wong, our relatives didn’t want to take away these fortunate components, even if he couldn’t be in the same room as nuts. They began to completely miss family get-togethers.

How families are advocating for change

Supporting a child with dietary allergies begins at home. Older family members in some Asian American households might not know about dietary modifications, particularly if they are from nations where common Western allergies, such as peanut allergy, are less frequent or underdiagnosed. Wong took advantage of the opportunity to educate her doubtful relatives about food safety by starting to hold family potlucks herself. She has successfully advocated for legislation to enhance EpiPen availability in schools and writes about her experiences and allergen-friendly Asian cuisine on her blog, Nut Free Wok.

Ina K. Chung and other parents are resisting stereotypes. Chung joined Facebook forums for allergy parents after learning that her 6-month-old baby had peanut, dairy, and egg allergies. There, she discovered a lot of support as well as a lot of false information about Asian food. Some parents, even fellow Asian Americans, wrote that they couldn’t trust the food at Asian restaurants and posted general cautions against them.

Why do you not believe the restaurant staff when they tell you how the meal was prepared? Some Asian American parents separated themselves from their own cuisines, which particularly disturbed Chung. The notion that all Asian cuisine is harmful is a reflection of unjust perceptions and a lack of knowledge. She dispels these myths on her Instagram profile, @theasianallergymom. Classic recipes from her early years, such as Korean chicken soup with kimchi, which are inherently free of common allergies, are featured in her blogs. Like Asian people, Asian cuisine isn’t homogeneous, and I want people to recognize that,” Chung added. She has also authored a children’s book to assist parents in teaching their children about self-advocacy and food allergies.

This empowerment has been mirrored in Chung’s family. She questioned the mother of the host at a friend’s birthday celebration when her kid was five years old: Is this cake safe for me? What did you make it with?

Chung remarked, “You could see the pride radiating off of me.” When it comes to advocating for allergies, those minor triumphs serve as my compass.

New treatments and hope

The acomicstrip is displayed on the wall of Gupta’s office. In one panel, an adult tells a child, “There were no food allergies when I was your age.” The grown child then informs another child, “There were food allergies when I was your age.”

There were no remedies for food allergies ten years ago. These days, children can be desensitized to allergens using skin patches and oral immunotherapy, which lowers the possibility of severe responses. Still, Gupta said, many Asian American families she sees remain unaware of these options, highlighting the importance of early diagnosis and education.

In 2014, Wong s son completed a clinical trial that increased his allergen tolerance from 1 mg to 1,440 mg of peanut protein, or about six peanuts. Although the family still avoids peanuts and carries epinephrine, he s no longer reactive to trace amounts in the air.

Wong shares this story to encourage other families to seek testing, treatment and tools like EpiPens to take control, rather than live in isolated anxiety. Now, she cooks alongside her son, re-creating the dishes she once watched her parents make. Together, they ve found a way to reclaim tradition and savor a new beginning.