Gloria Holland can still clearly recall a picture from her early years: a man standing outside his front door in just his underwear, begging that his home in Palm Springs, California’s Section 14 neighborhood not be razed. Before a bulldozer leveled the building and the man scrambled to safety, he ranted for a few minutes.

Holland, who is now 70, stated from her home outside of Atlanta, “I was 8 or 9 years old.” I had never seen a grown guy cry before. It caused trauma.

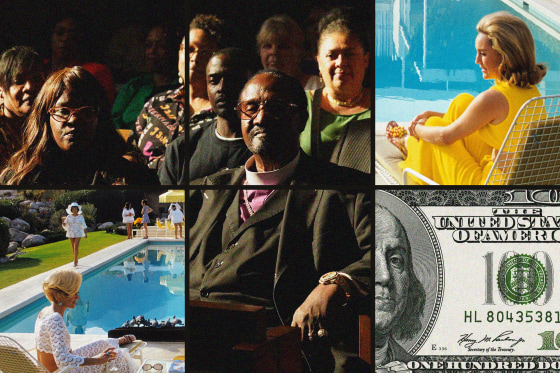

In the late 1950s and early 1960s, the man and Holland were part of 195 Black and Latino families whose homes were burned down and demolished with little to no warning. Native American-owned land had long been sought after by city officials, who wanted Palm Springs’ downtown to expand with upscale hotels and retail establishments, creating a metropolis regarded as a “celebrity playground” 115 miles east of Hollywood.

According to Holland, we were informed on Friday that we had two days till Monday to remove everything we desired from the house. That was it. It was terrible.

The Section 14 Survivors Group complained to the city in 2022, requesting compensation for the hundreds of homes that were destroyed and lives that were abruptly upended. A tiered settlement offer to previous inhabitants and descendants of individuals who resided in the Black and Latino neighborhood was unanimously approved by the Palm Springs City Council earlier this month.

During the hearing, Councilmember Lisa Middleton stated that the city of Palm Springs is accountable for paying people for the damage to their personal property. We must now compensate for the damage we caused to something that was yours.

The settlement includes direct cash payments of $5.9 million to 1,200 individuals. The city also decided to create a cultural healing center, a public memorial to the legacy of the former residents, and a communal park named in remembrance of the displaced. In order to rectify historical prejudice against its Black and Latino inhabitants, the City Council also approved $21 million in housing and economic development initiatives. Of these, $10 million will be used to create a community land trust and another $10 million will be used to support a first-time homeowner assistance program.

Additionally, a $1 million small company program will be funded by the city to support local business efforts for underserved communities.

“It’s been an emotional journey, ranging from sadness, anger, frustration, and excitement,” said Areva Martin, the lawyer who spent two years representing the Section 14 Survivors in their fight for justice. I was aware that many individuals, especially older Black people, find the reparations discussion challenging because they have been conditioned to live with, not complain about, repress, and in some ways forget the racial trauma they have had.

Martin explained that because many of her clients had never spoken aloud about what had occurred to them, she tried to persuade them to share their tales in ways they had never done before in order to ensure the City Council knew the impact of the displacement. Neither their children nor their grandchildren had been informed. Without a certain, they hadn’t discussed it in public. However, I was aware that in order to go on and heal, we had to admit the wrongs of the past.

It was challenging, Holland remarked. She claimed that going through this experience triggered many feelings and memories she had repressed.

She looked to be traumatized anew by going back in time.

She remarked, “I’m sure a lot of my neighbors felt the same way because they had similar stories and I could see it happening again in their faces.”

Holland claimed that her parents made an effort to normalize things and hide from her the drastic nature of the relocation.

My mother used to take me to watch the construction of the new house we were lucky enough to be building, she recalled. But I wanted to return to my former home. There, we had a community. Living there was a dream come true. We were safe. No drugs. No offense. They simply took all of that away from us.

The Agua Caliente Band of Cahuilla Indians possessed a square mile of territory known as Section 14. It was one of the few areas in Palm Springs where Black and Latino residents could live due to racial covenants in the 1940s. Commercial real estate developers became interested after the federal government opened up 99-year leasing agreements for the Agua Caliente Band and other tribes in 1959. Residents who worked as carpenters, plumbers, construction workers, maids, chefs, gardeners, and others in domestic jobs contributed to the development and upkeep of Palm Springs’ infrastructure.

Despite this, the city ordered the fire department to demolish and burn the houses after obtaining conservatorship over the land from the tribe in order to capitalize on luxury tourists.

The events at Section 14 were characterized as a city-engineered holocaust in a 1969 report by the California attorney general.

Beginning in 2021, Pearl Devers led the Section 14 Survivors group, which demanded that the city compensate them for the harm caused by the destruction of their community. According to Devers, she stood up for her parents, who endured greater hardship than we did. The adults endured that insanity. Our family was split up by it.

Her mother used to work as a maid for the renowned actress Lucille Ball. In Section 14, her father constructed their house. Her father, however, was denied a loan to purchase a new house when they were uprooted.

According to Devers’ mother, her father’s alcoholism was caused by racism and redlining influences. She said, “Our family was devastated.” My father never got over his drinking. At age 68, he passed away.

Without going into detail, Devers stated that her brothers missed having their father around. She claimed that she frequently ponders what her life and that of her family would be like if they had never been evicted.

The same is true for 77-year-old Lawrence Williams, who currently resides in Columbia, Mississippi. When he opened his front door to a man driving a yellow bulldozer, he was ten or eleven years old. Lucille McFarland, Williams’ mother, was informed that they had the weekend to prepare before he returned on Monday to demolish their house.

He remarked, “I still remember my mother sitting at that table crying.” My mother, who earned $1.35 per hour as a cleaner, lacked the funds to just move. She didn’t own a vehicle.

After visiting a local store, Williams and his younger brother returned with a few boxes. When they could, kids assisted their mother with packing. It was challenging, but Devers’ mother went Williams’ mother house looking. Eventually, she found a spot in a man’s hunting trailer without a kitchen or bathroom, some 15 miles north of Palm Springs. They were forced to use the nearby gas station’s restroom. Before obtaining a permanent location with additional assistance from Dever’s mother, they lived in those conditions for three months.

Williams described it as traumatizing. Throughout the entire summer, I was terrified that I would have to attend the all-white school. It’s like an old wound that bleeds again when you talk about it.

McFarland, Williams mother, is 101 and lives with him in Mississippi. When her son recently told her of the efforts to gain compensation for being displaced, she said, No, her son said. She finds it too traumatic. From Mississippi, she has witnessed the Klan. Then that happened in California. She s been traumatized her whole life.

The settlement has brought a sense of relief. Not the money, the survivors said, but the public acknowledgement of the harms committed.

Coming out victorious means everything for our parents, Holland said. They kept us standing, thinking about them in this fight. I told Pearl, I don t think I can go another year with this. We were tired, traveling back and forth to California to fight this. It shouldn t have taken this long to do the right thing.

Martin, the attorney, said while they all rejoice in the victory, their work isn t over. They want to make sure all the components of the agreement come to fruition. She calls this case the journey of a lifetime.

This was led by folks in their twilight years, she said. I mean retired folks, many in wheelchairs, on canes, walkers, failing health, folks who have been marginalized, villainized, forgotten, erased, and for the first time, seeing that their humanity and their dignity was being acknowledged. That s the victory.

Note: Every piece of content is rigorously reviewed by our team of experienced writers and editors to ensure its accuracy. Our writers use credible sources and adhere to strict fact-checking protocols to verify all claims and data before publication. If an error is identified, we promptly correct it and strive for transparency in all updates, feel free to reach out to us via email. We appreciate your trust and support!